The cartoons that became a hallmark of Molla Nəsrəddin earned a well-deserved reputation within and outside the Russian Empire for their sophisticated artistry and satirical content. Their style was and remains unique in Central Eurasia: clever caricature imbued with biting humor drawn in color that became increasingly vivid with the passage of time and advances in print technology. The persistent presence in the cartoons of the Molla himself as an archetypal hero rooted in Turkic folklore provided a populist voice daring to speak to all sorts of authority in opposition to public abuse, malfeasance, intemperance, demagoguery, indiscretion, obscurantism, and misogyny.

The most complete extant copy of the original publication is among the holdings of the Institute of Manuscripts of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Azerbaijan, with more limited collections housed in Russian and Finnish repositories; in general, their condition is rapidly deteriorating. Our first goal, therefore, with the Institute’s confirmed permission, was to digitize the collection and thereby ensure the preservation of this unique resource. That process has been completed. So to has been our secondary task: to translate the cartoon captions, interpret those captions and the cartoons’ content, and create a digital archive of the entire collection for global dissemination. In order to render the archive as useful as possible, we will make it searchable by date, name of artist, themes, and key words.

In addition to the project’s intrinsic merits, we hope that by bringing Molla Nəsrəddin and its satirical artistry to a global audience we will add to the repository that has remained heretofore largely focused on European and American exemplars. [See, for example, ……] At the same time, we will reveal the extraordinary role that the indigenously produced cartoon played in an Islamic society more than a century ago.

What follows is a brief introduction to the remarkable Azerbaijani satirical magazine published in the South Caucasus from 1906 to 1932. It grows out of a larger project designed to gather, digitize, and disseminate in a variety of formats, including the Internet, up to 10,000 cartoons that appeared in the Turkic-language periodical press of the Russian Empire. By far, the largest number of these cartoons were from the pens of skilled artists—two Germans (Oscar Schimmerling (1863-1938) and Joseph Rotter, and later the Azerbaijani Azim Azimzada (1880-1943)—in the employ of Molla Nəsrəddin’s founder and chief editor, Celil Memmǝdguluzadǝ (1869-1932).

From its inception until 1917, the eight—page weekly magazine was printed in Tbilisi, the region’s intellectual and cultural center for Azerbaijanis, Georgians, and Armenians. Thereafter, except for a brief time when it found a home in Tabriz, Molla Nəsrəddin rolled off a press in Baku.

Introduction

“All Russia is quiet and peaceful. The wolf and the sheep are grazing together.”

Telegram from St. Petersburg, March 30, 1906

“Muslims are progressing. A Russian pharmacist

has been granted permission to open a reading room,

so that nothing in Türkȋ may be read.”

Telegram from Shemakhi, March 30, 1906

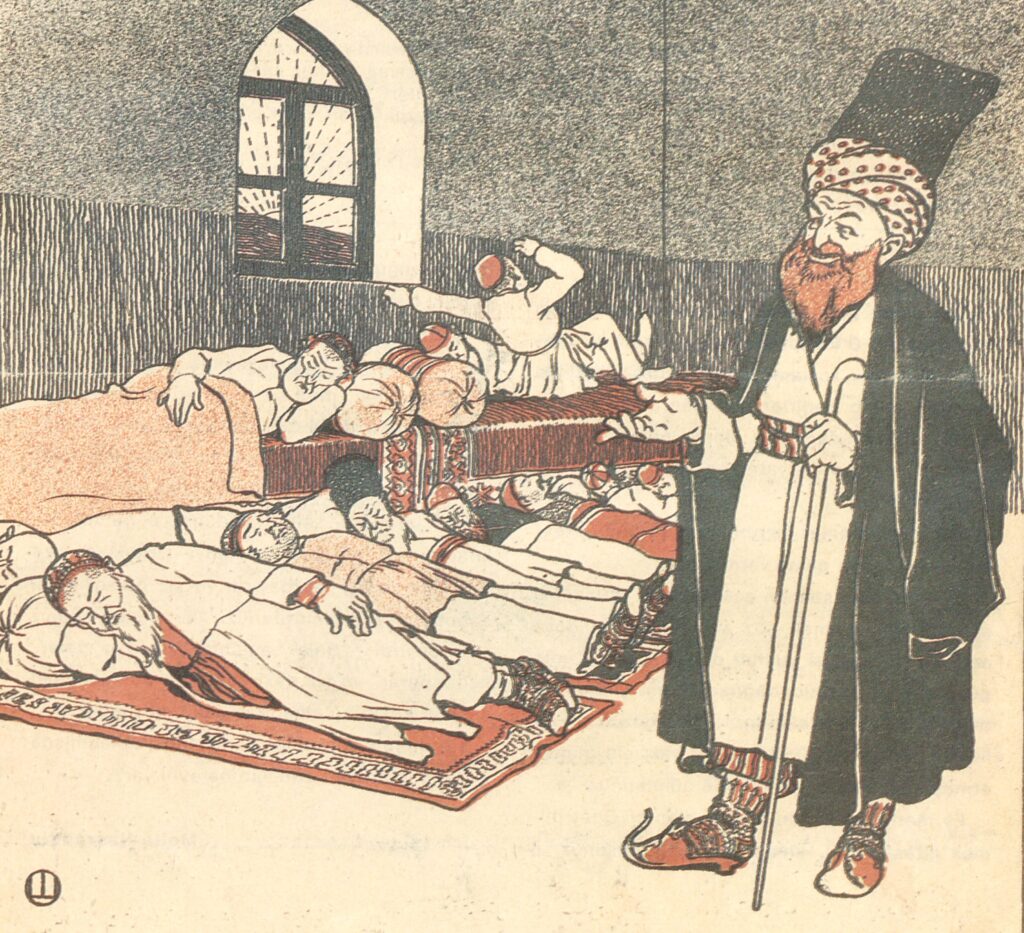

My exposition begins with two personalities, both of whom lack historicity, and only one of whom is human, although the other pretends to be. The first is known among Azerbaijanis as Molla Nǝsrǝddin, a man of humble, even self-deprecating character, who became an archetypal hero largely because he famously challenged nearly every component of social and political life with simple, mostly unintended, wit. He spoke in measured terms, not infrequently with hand gestures (see figure above), and effected a perplexingly fearless impression among his peers without a hint of heroic bombast. The second is named Snoopy, an extraverted dog with a Walter Mitty complex who lives out his days among human comrades, all the while offering his own witticisms in response to life’s pathos and existential burdens. Like Molla Nǝsrǝddin, he, too, is a fearless virtuoso at every endeavor, especially in his daydreams atop his doghouse, where he develops his alter-egos as novelist, fighter pilot, jazz musician, scholar, chef, physician, painter, baseball player, and big-man-on-campus. Facial expressions and thought balloons are his preferred modes of communication, and in their brevity, as with the Molla, resides everything that needs to be said. Both the Molla and Snoopy are wise beyond expectations, outspoken in opposition to public abuse, malfeasance, demagoguery, and indiscretion, making their audiences laugh first and then think more fully about what the two reveal through their populist philosophies. Both are man’s best friends for their unblinking honesty and faithfulness. As Snoopy reminds us, and the Molla would agree, “life is full of rude awakenings.”

When we speak of Molla Nǝsrǝddin and Snoopy, we must speak above all of satire, that genre of literature in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, governmental officials, and society itself into improvement. Although satire is usually meant to be humorous, its greater purpose is often constructive social criticism, using wit as a weapon and a tool to draw attention to both particular and wider issues in society. To be successful, satire must possess several characteristics:

- Be ironic, for without irony, it is merely literal and banal;

- Be humorous, for without humor, it is nothing more than criticism;

- Be militant, for without mockery, it is simple comedy;

- Be suitable, for without a deserving object, it is artlessly mean;

- Be clear, for without a patent argument, it cannot be effective;

- Be stealthy, for without stealth, it becomes vulnerable to easy rejection;

- Be efficacious, for without unnerving its audience, it cannot succeed.

To highlight these satirical imperatives, let me offer a simple, and current example in the form of a news item:

CRIMEAN VOTERS EXERCISE DEMOCRACY FOR LAST TIME

SIMFEROPOL, UKRAINE 14 March 2014—Following yesterday’s referendum in which 97 percent of voters cast ballots in favor of seceding from Ukraine and joining the Russian Federation, Crimean citizens expressed their excitement Monday at participating in the democratic process one final time. “It brought me such great personal joy to head to the polls and, for the last time ever, have my vote tallied and actually mean something,” said local businessman Sergei Petrov of his vote in support of annexation by Russia, echoing the enthusiasm of hundreds of thousands of his fellow Crimeans who proudly took part in their final opportunity to assert their collective will at the ballot box. “Yesterday was a historic day for Crimea. Our people had a say in their future, and our voices were heard loud and clear, which is extremely special given that it won’t happen again for who knows how long.” At press time, Crimeans were commemorating the vote to become Russian citizens by eagerly watching and reading coverage of the momentous event in the limited handful of sanctioned media sources they now have available to them.

What makes this news item work as satire is revealed in its very title, where the irony caused by an inherent contradiction between reality and expectations leaves a distinctive “after taste” in the observer’s mind. Here are a few additional news headlines to emphasize this point:

- Scientist Splits Atom, Finds Toy Prize Inside

- North Korea Warns Missiles can Reach US in Two Days via UPS

- Russia to Annex St. Petersburg, Florida

- US Apologizes for Biden’s “Hu’s on First” Routine

- Mystery Disease Affects One in Nearly Every Human Being

- Colorado Giggling for More than a Week Now

- Congress Welcomes First Open Bipartisan Representative

Or, to borrow from Jonathan Swift, who set the European standard for modern satire when he wrote A Modest Proposal in 1728 as a “solution” to the economic problem of poor children in Ireland: sell them to the upper class as food! In normal circumstances, cannibalism is a supremely distasteful concept; in Swift’s hands, it serves as a hyperbole for the general attitude toward the poor in Ireland during his lifetime.

Molla Nǝsrǝddin, the Satirical Magazine

Just after the turn of the twentieth century, a remarkable modern publishing venture made its debut. In the self-described Georgian city of Tbilisi, where the intellectual life of all three major ethnic groups in the South Caucasus flourished in close proximity and strove to lead their respective societies along a transformative path to an unimaginable future, the inaugural issue of Molla Nǝsrǝddin appeared on April 7, 1906. Taking advantage of the reform of imperial censorship laws that opened up extraordinary opportunities for publishing in non-Russian languages, the experienced writer Celil Memmǝdkuluzadǝ (1869-1932) launched an eight-page weekly magazine. The publication was remarkable from its inception for its style, format, and content. Amalgamating word and imagery in ways never before seen by an Azerbaijani audience, written in a language—severely modified Ottoman Turkish (Türkî )—simplified so as to be readable by the moderately literate, and employing superb artistry to produce some of the finest and cleverest visual humor anywhere in the world, Molla Nǝsrǝddin became a powerful advocate for modernity in a society just beginning to break away from its Celil Memmǝdguluzadǝ traditional commitments.

Between 1906 and 1932, with several interruptions along the way, the magazine produced issue after issue filled with what would become its trademark: militantly ironic satire, in words and visuals. Its targets seemed numberless: members of a perceived hypocritical and lascivious clerisy, useless intellectuals and nouveau riche, brutal husbands and fathers, authoritarian political leaders, cruel mothers and mothers-in-law, imperialists, pedophiles, and crass economic exploiters. The educational system, the family, religion, politics, language, generational tensions, social inequalities, ethnic relations, and the economy all received their fair share of caustic critique redolent of fearless and relentless honesty. Sacred pieties were continually stoned with rational principles and tormented by wit’s stinging lash. Ever present, the Molla himself can be found in the majority of cartoons, silent but nodding or gesturing with his hand toward the unfolding scene as if to say: “See what they are doing!” or, contrarily, “See what we can do!”

In 1909, at a time when the number of subscribers topped 4,000 annually, the decision was made to increase the issue size from eight to twelve pages. Within a year, however, a decline began as Memmǝdguluzadǝ became increasingly distracted by his literary interests, important contributors began to die or move on to other activities, and events started to interfere with the stability needed to maintain a complicated publishing venture. After its ninth issue in March 1912, the presses stopped for Molla Nǝsrǝddin, were restarted at the beginning of 1913, shut down again at the end of 1914, and remained quiet until a brief reprieve in 1917. The magazine closed down again after that year’s 26th issue. Although it would be published on and off from 1921until January 1931, at times in Baku and other times in Tabriz, its significance was severely hampered by the success of the Bolshevik Revolution and the post-Civil War consolidation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Liberal, moderately socialist, and committed to the jadidist program that inspired nationalist politics, Molla Nǝsrǝddin could not remain true to its principles when those became objects of unremitting attack by a regime with totally different goals and visions.

“Admonitions to Those Wishing to Subscribe to Molla Nǝsrǝddin” MN, No. 1 (April 6 1906)

First, it is necessary to ask God to grant his permission, to be revealed to you through a dream or omen;

Second, you must write to our office with a reed pen and Tabriz ink. By no means use an iron pen and Russian ink;

Third, do not permit the hands of the postal clerks to touch the subscription payment you will be sending. If their hands are sweaty, the money may become wet. If you follow this injunction, it will not be necessary to wash the money with water after it arrives at our office;

Fourth, write your letters to us in such a fashion that they do not contain a single Turkish word. Because writing in Turkish implies that you are lacking in education, do not shame yourself.

Fifth, during the following days, we do not deem it proper for you to subscribe:

- The 3rd, 5th, 13th, 16th, 21st, 24th, and 25th of each month because they are inauspicious;

- Tuesdays and Wednesdays;

- The 28th and 29th of each month, because they are the Days of Light, when it is not permitted to begin a new endeavor;

- The two days each month when the moon is in Scorpio, do not become a subscriber and do not begin a good deed;

- The twelve days each month that are regarded as the period of Eight Stars, during which one ought not begin a new task.

“News Everyone Should Know” MN, No. 1 (April 6, 1906)

For those who can answer the following questions, the Editor will provide the magazine gratis for the entirety of the calendar year:

- Why is it that in our primary schools only one out of twelve illiterate Muslim teachers can write his name despite deliberate groaning and grunting?

- In order for a Shi’i to drink water from a cup that a Sunni has used for the same purpose, why is it necessary to first wash the cup?

- Which is more plentiful, stars in the sky or the gambling places in a Muslim bazaar?

- How can bereaved wives of recently deceased men prevent the mullas from forcibly entering her home to partake in the ceremonial meal given to honor the departed?

- How can much needed books be procured so that Muslim boys can be taught in Türkȋ?

- Which countries’ enterprises are producing laziness and a lack of ambition?

- How is that the snakes arriving in boxes from Iran do not bite people other than Iranians?